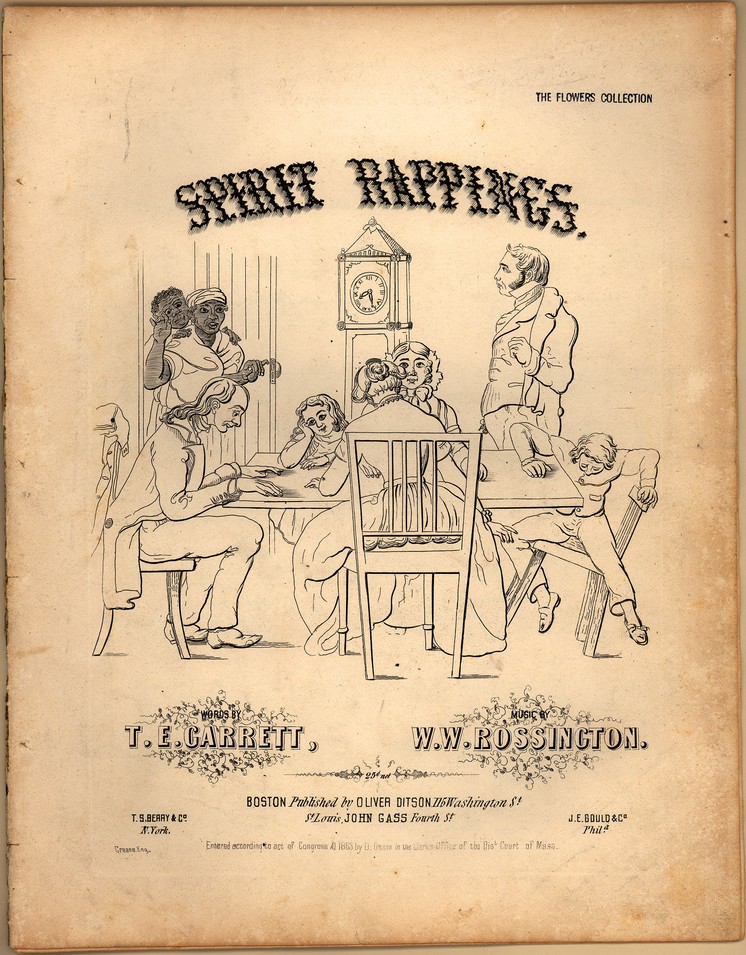

Conversation on the

Spirit Rappings #2 post wandered over to the idea of releasing songs in the form of the raw source files used for the final mix, starting with this comment of mine:

Releasing songs as their raw multitrack sources would carry this idea to its practical extreme. Every sample and every track would be preserved in the best possible detail. And why not? It’s true that these would be very big files, but bandwidth and disk space keep getting better.

Jay replied that this is doable, but misses the point:

The raw multitrack sources for my musical output over the last year are on the order of 25 gigs total. It’d all easily fit on any current iPod-like device or be inexpensive to store and serve up from Amazon S3 or Dreamhost.

It’s absolutely practical to now release many versions and raw sources of music online–it’s in many respects simpler to release 25 gigs of raw audio sources online than it is to get 650 mb of that onto a CD that is shipped to people.

But, at what point are we just talking about recorded sound objects vs music? Not that I think there is a big distinction that needs to be made in absolute terms, but rather in any specific relationship between music creator and listener (or, co-creator).

There is an art to the “release” of music, which reflects the process of curating, editing, aggregating, sequencing, packaging etc., as well as the relationship with the music’s potential audiences.

You can’t sidestep the need to make a definite statement, to say something specific, to be clear about what you aren’t saying. And given that, what does Jay feel he’s definitely saying with his music?

I see my own recorded music as creating musical instruments that other people play. I think everyone’s recorded music really functions in this way, but I definitely feel this way about my own. Everyone (who listens to or plays the music) makes it into their own music when they play it. And, with my own, I am excited by the possibility that some people will find creative and interactive ways to play it beyond just the songs passively showing up in the shuffle on iTunes. (But, even in the passive case, the music itself is interactive and can become your own–can change into something new and personal to you.)

And gurdonark articulated his experience as both a sampler and source of samples within the endless feedback cycles of the remix subculture:

I love the use of my own and others’ available sound clips as samples for manipulation and processing.

In an earlier time, one had to worry about concepts like “plunderphonics” to realize the possibilities in appropriation of sound. That idea seems more quaint than revolutionary now.

With Creative Commons and public domain sources, the whole paradigm shifts. I can go to the Freesound Project or the mixter or librivox or netlabels which permit sampling and snap up a recording of this or that. I can then sequence it through my 25 dollar softsynth and create something new. The sound is not just an instrument, but also a string, or a motif, or a loop, or even an indescribable discordant pad. The customary definitions are merely touchstones, old-technology concepts inadequate to describe the starchild of possibility inherent in captured open source sound.

When sound manipulation offers so many possibilities–most of which are accessible via use of freeware or inexpensive shareware–then the “buy my record, worship me, make me a star” thing eventually fades away into some obscure past. Collaboration and exploration step in and create arguably fewer fankids and groupies, and more pioneers and innovators.

Generations removed from peoples’ tastes tried to create a rarified form of music appreciation, accessible to only a chosen few. But now, the experience of being bathed in the possibility of manipulated sound creates huge niches of listeners no longer bound by the old conventions of how they “must” or “should” make music. Instead, new ways of experiencing music and sound can arise and evolve with quantum software-release speed.

I can take Lucas’ voice, and make it into a monastic drone. I can take his guitar and make it into a warm blur of gorgeous echo. Yet the fun begins when the next remixter takes what I create, and turns it into something new and unexpected. It’s no longer arty condescension to make some abstract point. It’s a swimming pool of sound, remixed and reveled within, and the water is just fine. That’s the possibility in open source music, and, like the myth of salvation, it’s available to all.

In my personal explorations of sheet music from before the recording era I have to think a lot about how that level of abstraction is special. Music notation is an incredibly skeletal way to describe or communicate a piece of music, and it changes the music to be written down. Writing out music sends the message that what is eternal about a composition is the selection and order of pitches, regardless of what instrument you play them on: it says that “this is song is ‘C’, then ‘B’, then …”. And I don’t know that this is *true*.