It’s opening day for Soup Greens, a new blog oriented towards my musical life.

The goals are:

- To improve viral uptake from live shows by giving people something to take away that can bring them back again.

- To make booking gigs easier by having a comprehensive resource to show to bookers.

- To get gigs as a sideman by having a standard URL which leads to samples of my playing.

- To simplify the work of distributing music online via sites like Facebook by having a centralized distribution point that I can link back to from third party sites.

- To own the digital identity and preferred URL for my musical work rather than letting third parties like Myspace own it.

This is the end of a long bootstrapping process, but at the beginning there was only one simple requirement. I was doing gigs and needed a way for people to take home music, primarily because I needed the shows to have more viral impact. The old school way to do this kind of thing would be a CD, meaning that the new site is a replacement for a CD in a lot of ways.

The really really old school way to approach the whole thing would be to sell CDs. I’d push to get them into stores, attempt to get them onto the radio, and attempt to sell them at shows. It took about two minutes to rule this out. For the purposes of viral spread, charging money would eliminate most of the people I wanted to reach. The money I could earn was negligible. Radio is an uncrackable nut and doesn’t matter anyway. Manufacturing would be a monumental pain in the ass. Distribution woul be a drag. And most of the CDs would end up in a box in my closet.

Then I figured I would low-ball the manufacturing costs with a barebones package and give the CD away for free at the shows. After I costed it out, though, that was a non-starter. The CDs would cost no less than a buck apiece and closer to $2 after you count in excess inventory. Most of these expensive freebies would end up in the trash before they got listened to. The response rate would be too low to return my costs. Free downloads have virtually no incremental costs, but free CDs certainly do, and I’d never break even with this approach.

My next idea was digital distribution at shows. I figured I would bring a USB stick and offer to let anybody make a copy who wanted one. In this end this wasn’t a bad method, it just wasn’t going to accomplish much. Partly that’s because not a lot of people bring laptops to rock bars. But also it’s because there is no way to get people to go from a raw MP3 back to my web site, where I could get them to go to future shows, book me, or invite me to sit in. You can’t do an effective upsell from an MP3.

Lastly I looked into doing a good Myspace page. You can see my attempt at that on the Myspace page for Alvin and Lucille, a jazz act I did last year. One problem I had there was that I couldn’t abide Myspace’s technical problems; the MP3s often cut off midway through or don’t load at all, the MP3 links aren’t exposed, and the Flash player just doesn’t work very well. The other problem is that Myspace would then own my identity and I’d have to either duplicate all that work on other social networks or stick with only Myspace.

So I started on a new web site of my own under the assumption that I could hand out cards with the URL at gigs. The card would be dirt cheap to print, cheap enough that I could afford to give them away. They would be convenient for people at the shows, who could stick one in their pocket and take it home without needing a laptop; URLs are incredibly lightweight to carry around. When they got home the card would be a reminder of what they saw, so would help with memory. And anybody who went to the site would be able to join a mailing list, send an email, or add me to their Myspace friend list.

The first problem was compelling content. Musicians’ sites are usually boring, stale, vain, and link-poor.

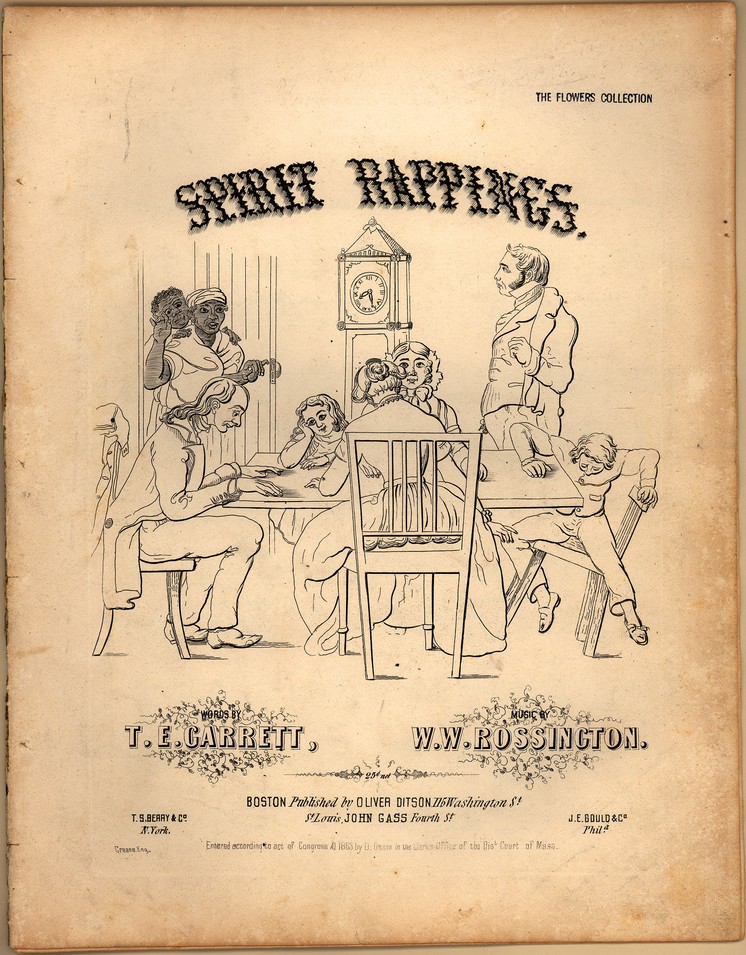

To fix the boringness I copied BoingBoing and expanded the scope of the blog to tangential fun stuff, including a post about buying shoes from the civil war reenactment scene, a post about hoop skirts, and a post about the Original Dixieland Jazz Band.

My biggest inspiration was Jon Udell’s blogging about his hometown of Keane, NH. This gave me the idea to blog about my entire scene rather than just about my own music, which is why I wrote the post about a ragtime pianist I met at a show and the post with songs by Madame Pamita. Jon’s witing about local life also let me feel comfortable with orienting myself towards completely meatspace goals. In the same way that nobody ever got laid on the net, nobody ever played virtual music, and in this project I didn’t care in any way about getting famous on the internet. My music is about being with people in the real world.

The other inspiration was Jonathan Coulton’s site for his own music, which is a lively place to hang out because it has a human presence and social tools. What I copied from him was the idea that a genuine blog would be the framework, rather than something with the brochure vibe you get from conventional musician sites. If I were marketing a hosting service for musicians I’d probably do the same, but for my own music I didn’t want to end up looking like this or this.

The last and hardest problem in all of this was identity. I’ve been doing tech blogging for more than five years now, so when I sent people I met while playing over to my established digital persona they got a bunch of technical gobbledigook and little music. The natural answer was to come up with a band name. Over the last six months I experimented with 7-8 different ones, including “Patsy the Barber”, “Slobbery Jim”, “The Soup Greens”, and “Alvin Pleasant.” Some of these were good, but none of them really worked because my true name is the most natural handle for me. The solution was to create a dedicated name for the music blog but use my own name as the blogger. That’s why the new blog is called “Soup Greens” and the tagline says “by Lucas Gonze.” This is a common pattern with blogs and I think it will work.

Next up I need to get viral spread going. It has to be a lot easier to sign up, subscribe, take away a widget, whatever. Also I need to print out something to put in people’s hands at shows. And the site still has plenty of usability problems. So I’m not done by a long shot. What I have accomplished is to break through all the fundamental issues; what I haven’t accomplished is anything that I can tackle incrementally.

I had a lot of fun making it, and I hope you dig it.

October 26th, 2007 at 8:00 pm It’d be interesting to map out the history of the “recorded music business” against recording artist needs.

Early on, there’s especially a need to access scarce technological resources (the means to record and manufacture physical discs). Then, later, there is especially a need to access scarce distribution channels (be part of a popular record label and/or genre outlet).

These days, the needs look more and more like “commodity” services, e.g., it’s about as hard to find a way to meet my need for a bookkeeper as it is to find a way to have my CD manufactured and sold (thanks to CD Baby for the latter!).

However, there are some cultural factors that come into play, as well. IMHO, being a successful musician means [having successful interactions with listeners. To the degree that any of the interactions cross into the realm of business, the musician needs to create (or work for, or buy into) a “successful business.”].

So, the “label” model has a function in that it provides a “business” for musicians who aren’t into or otherwise ready to create their own business. A lot of the “label” business models out there involve preying on musicians’ lack of business savvy.

There are also cultural reasons why people think in terms of genres and gravitate towards “trusted” marketing channels, aka the so-called “taste makers.”

{

Lucas responds:

}

October 26th, 2007 at 10:52 pm My ideal [“taste-sharing”] situation looks like what my childhood experiences were when a radio DJ’s shift was a *show*, authored by the DJ and reflecting their personalities (and ingested chemicals). They had fan followings for inventive sets with musical themes and soul.

Everybody appreciates all the good work [CD Baby and Tunecore] have done in enabling artists to simplify a boring part of their day and therefore indirectly cultivate their art. But I could make an argument that open music won’t have it’s break out moment through these massive online catalogs. They will break through taste sharers at which point the only services necessary for the artist are paypal and a remote host. Who is cultivating the taste-sharer? Who is enabling the next Ahmet Ertegün? (I’m aware of the many attempts at podcasting-enabling sites and I suspect many of them fell down for all the typical dot-bomb reasons).

October 27th, 2007 at 1:28 am Victor said: “I could make an argument that open music won’t have it’s break out moment through these massive online catalogs. They will break through taste sharers at which point the only services necessary for the artist are paypal and a remote host. Who is cultivating the taste-sharer? Who is enabling the next Ahmet Ertegün?”

I think the near-global importance of the Ahmet Ertegüns of the world is an artifact of late-20th century communication media. Before the 1920s, there were lots of people who influenced others’ tastes in music, but there were very rarely break out moments on the national or international scale.

We’ve always had thousands of “tribal” and regional tastes that had little basis of or need for agreement with each other. During the second half of the 20th century, we also had some shared national and international tastes that allowed for artists to attain large-scale popularity.

I think we’re returning to a world where tribal tastes are primary over any apparent global tastes. The webs of music online connect across online tribes of interest and taste.

I put “taste maker” in quotes because it tends to imply that there is some kind of “global” set of specific agreements on taste, and that there are a few people out there who help everyone globally come to these agreements and know the specifics. I think it’s all just a lot more fuzzy and distributed that that.

{

Lucas responds:

}

October 27th, 2007 at 3:05 am I agree that CDbaby offers artists a set of services useful to artists. I appreciate Derek’s post, as I’ve observed that CDbaby has worked for independent artists in just the way he’s described, as a resource for the indie to distribute product. So many times artists need one-click convenience for ministerial but important business things, and that’s what artist services offer. I love hearing things like “this will show up on your credit card as CDbaby” instead of “I can only take cash, and I don’t have any more change”.

I still think that Victor has a point about taste-makers (personally, I put things in quotes or not in quotes according to the guiding rule of whim). I do think that new taste-makers will arise and are arising. I agree with Victor that nobody much expects/wants/falls for “being told what to listen to”, but I do think that gifted people have always helped find cool stuff in popular music.

My own feeling is that new taste makers are arising, and will continue to arise. I find the most useful ones to be websites, whether it is biotic’s black sweater white cat or gorilla v. bear or, for my own beloved genre as a listener, ambient music, the forum at www.hypnos.com.

Victor’s point is a powerful one. When I was a young teen, one listened at midnight to one particular radio station in Chicago to figure out what was cool and new. Did we accept that station’s DJ’s judgment as gospel? No. We took and we discarded. A similar thing happened with Bingenheimer in Los Angeles, on an even larger scale with Peel in the UK. On a recording front, the Stax sound was not sheer serendipity, but a set of choices made not only by musicians but also by record-company-types who believed in them.

The technology now exists to liberate us from the market dominance of record labels. Yet as Derek and Peter Wells both point out, their companies are to serve artists and not to replace labels. They bundle services to make artists’ lives easier.

Jay’s point is right in that the construct of how we thought about labels no longer need apply. Among the essential industries that must arise in this era of “commodity services” is effective ways to “get the word out” on signal amid noise. Don’t get me wrong–there is no one signal, and noise (believe me) is delightful. But a community of music lovers benefits from people who help create community through recommendations.

I don’t read Victor at all as saying that there is One True Global Taste which taste-makers can point to (indeed, Victor would be the absolute last person to say so). Yet the sense of shared commmunity which taste-makers provide is one thing that binds similar-minded listeners together in their musical interests. I still believe that such taste-makers will inevitably arise (and are already arising), but I don’t deny that they’re a good thing. I just think, as Derek suggests, they need not be part of a record label (or, to extend the point, cdbaby or tunecore).

At the same time, I don’t really disagree with Jay so much as see the “tribal” nature of music spread as inevitably including taste-making on a big scale. The tribes are virtually bigger, so to speak, even as the niches get smaller.

I have a bit of nostalgia for times when I was 13ish and Lisa Robinson was putting out a teen photo magazine which told me about these incredible unsigned bands called the Ramones, the Talking Heads, and Television (or, now that I think of it, Wayne/Jayne County). Those were heady days, when one could find destiny in a pulp magazine at the local IGA grocery. That kind of taste-maker was an essential and wonderful thing. Finding that kind of taste-making again will be the liberation of artists from the old record label paradigms. The technology makes it every bit as possible and inexpensive for them to arise as using tunecord and cdbaby. It just requires practicality amid the visionary dreams.

In the communitarian (archive.org) v. Ahmet Ertegun divide, my sympathies are definitely communitarian. I favor free download music, Creative Commons BY licenses, and a conspiracy of user/hobbyist/creator/fans to share culture.

But I believe that the era of artist services and indie direct releases will benefit as taste-makers arise. We see the first embers, but the burn is inevitably going to come.

Let’s take a simple example. A few years ago, a weblog friend of mine named CP McDill announced that, having sold only a handful of CDs as an artist, he intended to start a Creative Commons netlabel. He would release his albums for free under his Webbed Hand Records netlabel, and then release other artists as well. Webbed Hand releases were soon rather popular in the way of such things, because the label’s experimental/dark ambient “branding” meant that people knew what they were downloading when they downloaded a Webbed Hand release.

A free album on Webbed Hand is not directly analogous to a commercial release (being on the communitarian side of the fence). The idea, though, plays on the commercial side of the street, I believe.

People will arise, whether journalists, website maintainers, label owners for a new type of label, or webloggers, who will help create this kind of “branding” and association. This is not the robotic “look into my eyes, you are getting sleepy” hypnosis theory of forcing style down one’s throat. This is organize style-making. But until those style makers have the sway of late night Chicago rock radio blaring 100,000s of thousands of watts across the midwest and south, then the rocket has not yet launched.

My optimism, though, is that this rocket will indeed launch. My belief is that the next fame/money/glory will go to the people who figure out how to light the way the way that the talented locators of talent once did. I don’t care who emplys ‘em–I just care that we all connect to the cool music.

{

Lucas responds:

}

October 27th, 2007 at 6:20 am I don’t know if there can ever be another, say, Ray Charles–because Ray Charles is the combination of a great talent and a no longer existent world boxed in by nascent inter/national media.

Imagine, in 1955, when “I Got a Woman” went to #1 in the US, how many other R&B artists were out there who never ended up getting a chance to make records, and whom we’ve now never heard of. Or ones who cut a 45 that is now lost to obscurity.

I don’t know that we’d see Ray Charles as such an amazingly legendary talent if all of those other artists could have made albums, and we could hear them a lot.

And, looking at it the other way, people don’t know that the Motown girl-group, The Velvelettes are great because The Supremes, etc., were the ones Motown turned into legends, circa 1964-65.

It’s not that Ray Charles or The Supremes are made less talented by suddenly being seen against more obscure contemporaries. It’s just that there’s less space for them to be legends on a pedestal.

October 27th, 2007 at 9:32 am Jay, at the same time that you make an excellent point about “finding a Ray Charles”, I also believe that the wonderful thing about ‘net culture music is that there is every prospect we will after all learn who is a next Ray Charles—and he may be uploading from Mali, or Greenland, where before he or she would toil in solitude.

{

Lucas responds:

}

October 27th, 2007 at 5:31 pm Gurdonark, yes. The more I think about it, too, the more I think we’ll keep seeing the figures behind the music we love as being legends in some way. Probably just more legends, more often.

p.s. I really like your “Roadrunner” — listening now.

{

Lucas responds:

}